Brooklyn company employs more than 100 blind workers

Originally published the New York Post on July 23, 2017. Written by Vicki Salemi.

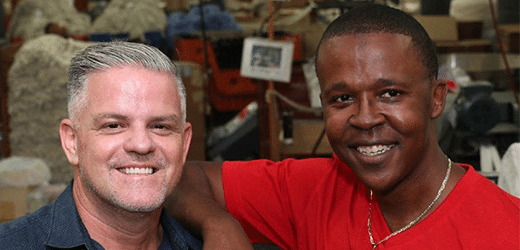

When Ted Rios turned 50 recently, his co-workers threw him a surprise party at a bar near their Borough Park office.

“It was amazing! They told me how much they appreciate me and what I do,” says the sales manager at Alphapointe, a 106-year-old company that facilitates manufacturing, third-party product assembly, warehousing and product fulfillment for city and state agencies.

Sure, it sounds like a typical celebration for social New Yorkers, but there’s an additional detail.Rios, from Bensonhurst, initially started working there 13 years ago as a machine operator and is legally blind, having been born with a visual impairment. He and 129 blind and 100 sighted employees comprise the workforce he refers to “as family.”

Damian Martin, an Alphapointe production supervisor from Bay Ridge, manages 40 direct reports.

Legally blind his entire life, Martin ensures orders are filled on a timely basis. He vividly recalls getting trained by his supervisor nine years ago upon employment. “He treated me just like he’d treat anyone else who was typically sighted. Straightforward. He didn’t approach the situation any differently from how he’d train anyone else,” says Martin.

Reinhard Mabry, the company’s president and CEO says that, when it comes to accommodating employees, the company uses whatever format someone needs. “If they need Braille, large print, audio, whatever adaptations they need, we provide them. People are onboarded in the same manner whether they are blind or sighted. We provide training they need to be successful.”

Company training includes fully sighted employees, too, who receive sensitivity instruction and exercises aimed at giving them a glimpse into the visually impaired world.

“This includes learning how to navigate the workplace with assistance while wearing sleep shades,” says Mabry.

In addition to its manufacturing role, Alphapointe also has an in-bound marketing call center, through which it advocates and places legally blind individuals in other companies. Employers with reservations about hiring someone who’s legally blind are typically unable to envision how that person can perform functions of a job, says Mabry. “It’s due to their assumptions of how they would fare if they lost their eyesight.”

There’s also a disconnect: the unemployment rate among Americans who are blind is approximately 75 percent, and yet a 2013 DePaul University study showed there’s less job turnover among blind workers and that they typically take fewer sick days than fully sighted workers.

In addition, there’s an employer tax break related to this hard-working population. In New York, the Workers (with Disabilities) Employment Tax Credit can result in a $2,100 reimbursement to companies for each disabled individual hired, with no upper limits to the number of hires.

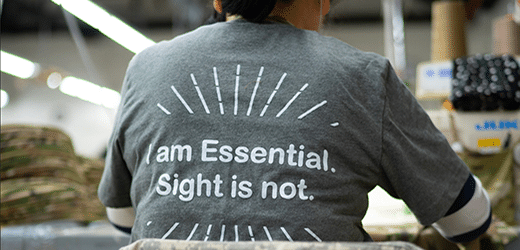

A major misconception, Mabry notes, is that people with disabilities aren’t as capable as others, and that’s simply untrue — a myth that Alphapointe also aims to dispel, one employee and external job placement at a time.

“People who are blind are capable, productive, skilled and loyal employees when given the opportunity to prove themselves,” says Mabry. “Truly, hiring someone who’s blind is the same as hiring someone who’s sighted.”

Rios concurs: “We’ve had colleagues who are completely blind ride the subway from Long Island to work. They put themselves through school, move up the corporate ladder. There’s no limit to what we can do given the right training and the proper setting. We’re capable of doing anything.”